by Michael H. Fox

When the post-war occupation forces were designing the present Japanese constitution, one of their goals was to broaden the sphere of rights encompassing the individual citizen.

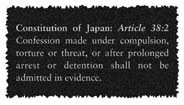

A key beneficiary of these rights was to be the criminally accused. Those accused of capital crimes would be presumed innocent until proven guilty, would not be admitted as evidence and if found innocent, the defendant could not be put in double jeopardy - the prosecution would forfeit the right to appeal decisions of "not guilty." However, a recent incident in Kansai demonstrates the contemporary treatment of the criminally accused and the gap between legal theory and courtroom practice.

THE INCIDENT

On July 22, 1995, Shimada Tatsuhiro, a 34-year-old electrician, stopped at a gasoline stand and filled the tank of his van before arriving at his home in Osaka's Higashi-Sumiyoshi ward. Ten minutes later he smelled smoke and noticed a small fire in the garage under his van. He quickly searched for an extinguisher while his wife called the fire department. Some neighbors also lent assistance, but the fire grew and spread. The couple's 11-year-old daughter, who was in the first-floor bath, tried to escape, but was overcome by smoke and died of asphyxiation.

Both the police and fire departments carried out detailed investigations. Japan has a proportionately high number of arson-for-insurance fraud incidents and so investigation is a routine matter. The fire itself did not arouse the suspicion of the authorities, but the circumstances of the family probably did. Police soon learned that the man and woman of the house did not share the same name, nor were they legally married. They had lived together for six years - a common-law marriage - and their two children were from the woman's (Aoki Keiko) previous marriage. Police also discovered that Shimada was a zainichi Korean (whose real family name was Boku) and that Aoki had life insurance policies on both of her children.

Life insurance coverage for children is not unusual in Japan, most couples carry it as a matter of course. The usual coverage for minors through major programs is ¥5 million, which can be doubled to ¥10 million for a nominal premium. Aoki's daughter was insured for ¥15 million, somewhat above the national norm.

THE INTERROGATION

The investigation of the fire did not seem to produce any suspicious findings. However, at 7a.m. on Sunday, September 10, some six weeks after the tragedy, a squad of detectives arrived at the couple's new domicile and requested both Boku and Aoki to come to the police station for voluntary questioning. Each was taken to a separate station. This questioning soon turned into an interrogation and the police demanded that each confess to arson, murder and insurance fraud. When Boku refused, his interrogators became violent. They hit his head, kicked his knees and applied choke holds. After 14 hours of continued verbal and physical abuse, police lost patience with Boku and fabricated a story saying his eight-year-old step-son had already confessed to seeing him start the fire. In a state of despair, Boku broke down and signed a confession admitting to the charges. Aoki received similar treatment and by eight o'clock that evening, psychologically broken, she had signed a similar confession. The next day, both were visited by lawyers. Both denied the charges, Aoki in tears.

CONFESSIONS: THEORY AND FACT

This case illustrates many problems of Japanese policing, particularly the function and the public's perception of confessions. A survey of various reference books touching on the Japanese legal system uncovers some disturbing commentaries which all but heap praise upon the present system. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Japan asserts that incarceration and long interrogation of suspects without the presence of legal counsel, a condition unimaginable in other industrialized countries, enables the police to "develop a human relationship with the suspect, to the end of obtaining a confession or, in many cases, multiple confessions."

Assertions such as these are frequently made by Western scholars of the Japanese criminal justice system. In a recent issue of this magazine (KTO 285, Nov. 2000), a foreigner who had problems with the law advises, "If you did it, confess. If you didn't, fight." Most readers probably paid scant attention to this remark, finding it painfully obvious. But because many ordinary Japanese appear to be oblivious to law and obedient to authority, police are often free to act as they please.

THE REENACTMENT

As the constitution of Japan prohibits conviction based solely on confession, prosecutors sought other evidence to cement their case. The police allege that on the day of the fire, Boku stopped in at a local store and bought a simple plastic pump, the ¥100 variety used for kerosene stoves in the winter. Upon arriving at home, he parked the van, pumped out six or seven liters of gasoline, laid the pump under the van and ignited the fire with a disposable lighter.

In order to support this story, the authorities commissioned the Scientific Criminal Investigation Laboratory, a governmental organization, to carry out a reenactment of the case. The institute is quite meticulous. It procured a similar vehicle, built a garage to the same specifications as Boku's, spread seven liters of gasoline on the floor, turned on some video cameras and set the entire thing ablaze.

The results of this reenactment were problematic and digressed from the evidence left by the actual blaze. In the reenactment, the paint on the van burned evenly and the rising smoke covered the ceiling uniformly. In the actual fire, the paint on the van burned linearly and the smoke marks were spotty and uneven. This evidence, confirmed by witnesses who gave statements to the police, points to a small fire which gradually grew, not the sudden blaze recorded by police cameras.

How then did the fire begin? According to a report drafted by Mochizuki Hideaki, a technical investigator who belongs to the Institution of Professional Engineers, the most probable cause were sparks from the air compressor that ignited gasoline that had leaked from the fuel-line canister. Boku had overfilled the tank at the gas station and a small quantity of gas had probably escaped from a crack in the canister or other places in the fuel line. The problem with the air compressor, made by a subsidiary manufacturer, was so widespread that Honda and other manufacturers issued a recall in 1991.

Defense attorneys have challenged other allegations made by the police. As a witness they called the owner of the small store where Boku is alleged to have bought the plastic kerosene pump used to spread the gasoline. The owner testified that he had no recollection of Boku ever purchasing such a pump nor, for that matter, of any customer ever requesting one in the middle of the summer.

After nearly 40 hearings for Aoki and Boku in separate trials, the Osaka District Court issued judgement. On March 30, 1999, Boku was sentenced to life imprisonment. Some six weeks later, Aoki was sentenced to the same.

AN ATTEMPT AT EXPLANATION

The lingering question in this case is "Why?" In Japan or anywhere else, law enforcement authorities are considered to be protectors of the peace, a force against crime and social disorder. But in many cases, the struggle to convict a suspect has no more ethical foundation than a soccer match: two teams, prosecution and defense, compete against each other with one objective: victory. The judge's decision (99.5% of suspects in Japan are found guilty) certifies the result and the game is validated for the police and prosecution, and unfortunately, in the eye of the public.

In any trial, it is difficult to elucidate all the factors that motivate and influence both the procedures and the players. It is quite possible that police and prosecutors have an ulterior motive in this case. I asked defense attorney Saito Tomoyo if discrimination had played a role. "Boku had never revealed his Korean identity to his wife's father," she explained, "and after both were arrested, Aoki's father, upon hearing the name Boku for the first time, asked a detective who he was. The response was 'Oh, you didn't know your daughter was bedding down with a Korean?'"

THE CASE CONTINUES

After the sentences were handed down, the defense teams immediately appealed to the Osaka High Court. Though the Japanese constitution guarantees the right to a speedy trial, the appeals process did not begin until July 2000, 14 months after initial sentencing. In an opening statement before the court, defense attorney Ogawa Kazue attacked the validity of the confessions. "What would an ordinary, middle-class couple without financial difficulties have to gain from that amount of insurance money? How could they know that the fire would spread and the smoke would rise with the necessary precision to kill their daughter? If this was in fact a conspiracy, is it really possible that an ordinary couple could engineer a master crime in which the evidence points to an accident and devise a plan which specified details of how and when to call the fire department, what lies to feed the police, what belongings to remove and where to live after the building was destroyed?"

Let us hope the high court deliberates these questions and the many other contradictions in this case before it issues a decision.

Problematic Crimes Involving Confessions

Sayama Case (Saitama, 1962)

A case that became a rallying cry for anti-discrimination groups, a young burakumin confessed to rape and murder. The confession included authorship of a well-written ransom letter - highly problematic since the accused was only semi-literate. He was released from prison after serving 32 years, in 1994. The case is being appealed.

Kabutoyama Case (Nishinomiya, 1974)

Two mentally-impaired children at an institution were found drowned. After 16 days of morning-to-evening interrogation, a young governess confessed to "unconscious murder." She was soon released, sued the police and was re-arrested and tried four times before final acquittal in October of 1999.

Kaizuka Case (Osaka, 1979)

Five men, four of whom were minors at the time of the crime, confessed to rape and murder. All pleaded innocent in court, but were sentenced to serve between ten and 18 years in prison. After finding that police used undue "physical and psychological coercion," the court declared four of the defendants innocent in 1986, the fifth in 1989. Ten years later, the defendants were awarded ¥12.6 million in compensation.

Midori-so Case (Oita, 1981)

After insisting on his innocence, a young man confessed to the rape and murder of his neighbor while "sleepwalking." He was sentenced to life imprisonment in the first trial and declared innocent in the appeals case.

Note: Michael H. Fox is director of the Japan Institute for the Study of Wrongful Arrests and Convictions, www.jiswac.org

An earlier version of this article was published by Kansai Time Out magazine in December 2001